Long before Helene, IV fluid shortages plagued hospitals

Before Hurricane Helene forced the closure of a manufacturing plant which supplies intravenous fluids in North Carolina , calls for concern in hospitals all around the country, many of the most basic intravenous fluids had already become scarce in the United States.

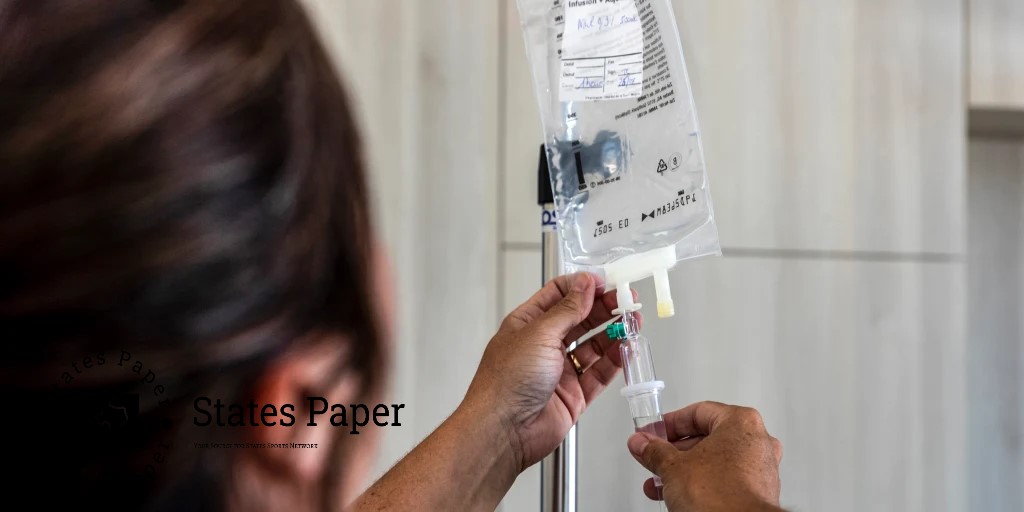

A 0.9% saline solution, sodium chloride and water, has been in short supply since 2018 which could also be found in the Food and Drug Administration drug shortage list. Medications with such solution such as saline drips that mostly contain solutions used for hydration are very common in hospitals. And there has been a shortage of sterile water since 2021; sterile water is an accompaniment to medications, an ingredient for diluting other liquids and also a cleaner for wounds.

And several concentrations of dextrose, a sugar solution to aid patients who cannot chew, have low blood glucose or require added calories, have been scarce since early 2022.

Last week the FDA said that shortages resulting from Helene’s actions also include other Baxter International products manufactured in North Carolina; for instance, another focus of the dextrose solution, an electrolyte solution called lactated Ringer’s, and a peritoneal dialysis solution for kidney failure patients.

Well, then why is the supply of these important and, in fact, lifesaving building fluids a difficult question?

As with a lot of drugs out there, it begs the question of money, and IV fluids do not generate a lot of it for the manufacturers, added Erin Fox, the senior pharmacy director of the University of Utah Health.

“These are products that save lives as we know but simultaneously these are very much like commodities,” Fox said.

This high entry barrier coupled with the need to recoup costs of meeting various regulatory standards to establish a manufacturing facility and the ever increasing pressure to keep prices low is not really encouraging drug makers into the market Fox said.

IV fluids, she said, also require an extraordinary amount of space: As an individual bag of saline may be as large as a loaf of bread and is likely to weigh just over 2 pounds.

“So not only open space but also should be strong enough to bear some weight,” Fox said.

To make matters worse, these products cannot be produced easily — not even sterile water/saline solution.

I see them go like, ‘It’s just salt and water!’ What do you mean?'” Fox said. “However, ensuring that all is as clean as they need it to be and free from accidental specks and contaminants and safe to inject into someone’s vein is a lot of work.”

Michael Ganio, senior director of pharmacy practice and quality at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, which monitors drug shortages in the United States, said an issue is endotoxins, toxic substances in bacteria that lead to a severe anti-inflammatory response in the body, including inflammation or fever. Endotoxins are heat and chemical resistant, and hence their presence must be constantly checked and controlled during production.

“You have these multiple tests that go into these generic injectables, and yet, the prices don’t speak of so much of that extra effort that has to be put into it,” Ganio said.

In the U.S., the IV fluid market is sustained primarily by four manufacturers: It was producing about 60% of the country’s IV liquids; B. Braun Medical, which contributed to about 23%; ICU Medical and Fresenius Kabi.

Fox said that means when one manufacturer shuts down, it hits U.S. hospitals hard, On the other hand.

“Any little glitch in the system can really disrupt things and create some shortages,” said Fox, who added that her hospital has not had any IV fluid shipments since late September. “Unless we are going to pay these companies to have extra capacity that is sitting there waiting, this is a shortage that we can’t stock our way out,” he said.

That is why today the Government has appealed to the wartime power.

Hospitals have gotten used to scenarios we saw with Baxter’s facility being closed; this was said by Dr. Chris DeRienzo, a neonatologist and the American Hospital Association’s chief physician executive. The shortage occurred this year after Hurricane Maria physical destroyed three IV fluid manufacturing plants in Puerto Rico all from Baxter.

“While this specific type of shortage on those specific IV fluids is not something, which we have experienced,” DeRienzo said. In addition to IV fluids the North Carolina Baxter facility also prepared specialty fluids including peritoneal dialysis fluid used to flush the abdominal cavity as well as irrigation fluids used to wash out a wound or incision site.

In the case of the Baxter closure for example, the federal government has been keen on scrambling to fill in the void. Last week, the Department of Health and Human Services said it used the Defense Production Act, a wartime authority that will aid Baxter in acquiring something to clean and repair its facility. In the law, Baxter will have first right on any materials that are scarce or even if the supply is cut and funding to increase on the production.

The FDA is also temporarily permitting Baxter blending in merchandise from subordinate factories in Canada, China, Ireland and UK.

On Tuesday, an HHS official said the actions had resulted in the increase of IV fluid products four times compared to what the center had few weeks after the shutdown of Baxter plant. Some hospitals had been complaining that they were receiving only 40 percent of their normal stock from the company.

Ganio added that these measures will not address the long-term concerns on shortages of IV fluids.

It may need rewards like assurance that in the future companies will be able to turn profits on their products. This is a big problem for the rest of the generic drug market as well, he said, including for other drugs in short supply such as cancer treatments.

Well, actually the IV fluids can be cited as one of the examples how chronic shortages look like, he continued.

Asif Reporter

Asif Reporter