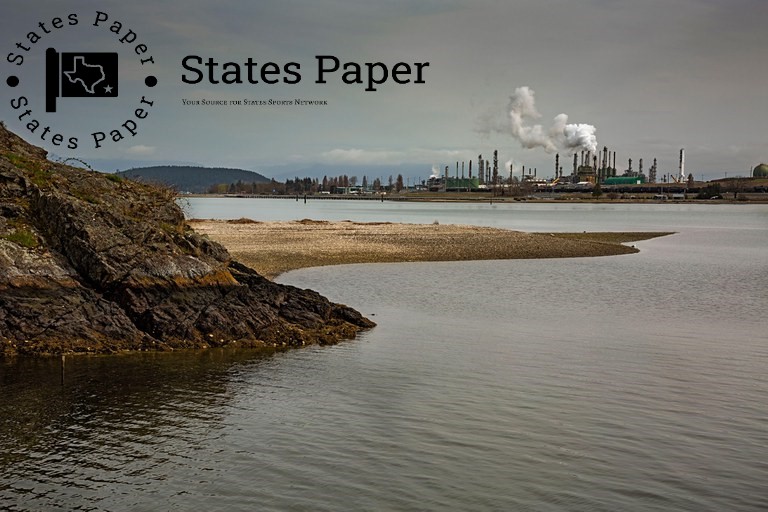

Washington lags behind in water-pollution oversight

State officials have been missing Clean Water Act deadlines for a decade.

A new study conducted by the GAO indicates that Washington state’s list of polluted waters is – years old. This may affect the cleanup of waterways across the state and water quality in Puget Sound, which may introduce more difficulties to the three species of endangered salmon.

It is expected that states should collaborate with the federal government in ensuring that rivers, lakes, oceans and wetlands are not polluted and remain healthy. Each state submits an updated list to the EPA every two years regarding water bodies which do not meet specified criteria of the federal Clean Water Act (section 402(a), regulating point source water pollution - industrial facilities, etc.).

We call these lists of “impaired waters.” We created them so as to provide Congress, federal and state agencies, tribal nations and the public with up-to-date water-quality information. For instance,” Washington’s impaired waters list, includes such problems like low level of The list may be used by some tribes, other governmental agencies, and other stakeholders to determine clean-up priorities and inform funding decisions.

For ten years now, the Washington State Department of Ecology has been behind schedule in meeting its deadlines to submit these lists. In 2015, the impaired 2012 list was submitted. In June of 2015, lists for 2014 and 2016 were submitted by September of 2021, with the 2018 list not submitted till September of 2021. There are also deadlines for 2020 and 2022 lists overdue that should be taken into consideration. (The EPA has been tardy, too: Despite this, the EPA has identified only three states including Washington whose 2020 and 2022 impaired water lists have not yet been filed. In fact, in 2018, the agency took 9 months before completing their initial evaluation for Washington’s

Thus, why is Washington lagging behind? State officials explained that the large numbers and complicated nature of water bodies in the state, plus the data generated by other agencies, required time for consolidation. According to Vince McGowan, Ecology’s water-quality program manager, Washington has one of the largest data sets in the country. He stated that a new data automation slowing down the current assessment, but will be useful later as increasing efficiency of the assessment.

“Never will we make any compromise in both qualities and engagement of that list.”

On his part, McGowan said the consultation involving the 29 tribal groups recognised by federal authorities in Washington State, in addition to Puget Sound having the right to fish, has prolonged the exercise. He said: “The list matters and we are using it to determine big things over time”. However, this is not something that we are ready to give up on both the quality and interaction to this list.

Professor Joel Baker, University of Washington, head of Puget Sound Institute; states that Ecology in general “does a pretty good job” regarding water quality and management. He, however, termed it a reasonable complaint. I do not agree with Ecologies claims that the work is more rigorous in Washington, he said.

In August 2021, Republican U.S. Reps., including Cathy McMorris Romers from the eastern washington and dan newhouse, and also Cliff Bentz from the Oregon requested the GAO report. Since then, they have used that report to chastise governor Jay Inslee for working to protect salmons. Three of the representatives vehemently reject the decommissioning of four dams down the Snake river while Inslee, arguing that the decommissioning in the present is impractical, holds that it could be practicable in the future. She wrote, “Ecology disagrees that it is primarily the timing in its listing of the impaired Washington state waters as one of salmon’s recovery factors. """

Our watersheds in the Northwest are achieving great success”.

According to David Herrera (chairman of, among other things, the Environmental Policy Committee of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and member of the Skokomish tribe), though he felt alarmed while first reading the report, after reading it more carefully, he “wasn’t really Other efforts towards salmon protection are ongoing, he said, and they include habitat restoration undertaken by the Skokomish Tribe and others. The Chinook and Sockeye salmons once again swim in the Skokomish River, which is where they were driven out long ago. “Some of our water sheds in the North west are doing well,” Herrera said.

Indeed, water pollution from industrial areas poses another serious threat for the state’s salmon, but certainly not the only one. The fish faces many other threats than those on impaired water lists—warming waters due to climate change, habitat degradation, and non-point source pollution that is unregulated under the Clean Water Act, such as agricultural or storm runoff. The GAO report recommended that Congress revisit the legislation’s “largely voluntary approach” to nonpoint source pollution. Herrera agreed: He said; “the key concern is that voluntary programmes cannot be depended upon.” A number of tribes argue that tougher law enforcement is needed to improve compliance. “The state’s not there yet,” a lot of tribes say.”

Staff Reporter

Staff Reporter