Warehouse advance in Riverside County threatens rural lifestyle: ‘Where does it stop?’

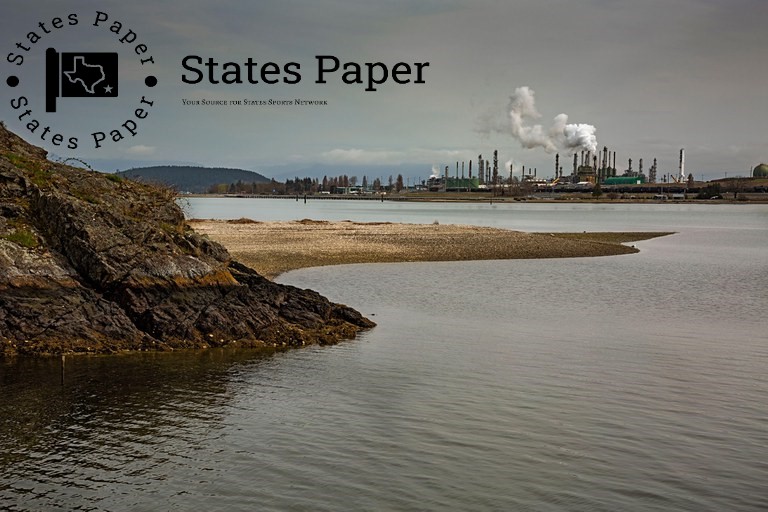

Looking down from a plane, the hundreds of behemoth warehouses hulking over Interstate 215 as it cuts through Mead Valley look like a great sea of shiny white cement cubicles.

While big-box distribution centers that handle online purchasing fulfillment are completely sited to a vast strip west of the interstate freeway in this unincorporated area of Riverside County. Other industrial users of 49 warehouses in this area include Burlington of Living Spaces and FedEx; Most of these industrial entities benefit from the railway points and freeway links in Mead Valley.

Outside of this strip, however, The Mead Valley residents lead rural life. Folks around here are ranchers and farmers who rear horses and other forms of livestock; many of the roads are paved with trails that support equestrians more than pedestrians. The only other types of businesses in the community are the gas stations and feed stores as well as plant nurseries and the new Farmer Boys restaurant located near the freeway.

With the onset of the COVID pandemic, e-commerce thrived and more distribution centers began to be developed near the freeway which means more trucks on local roads. However, there was knowledge that the rest of Mead Valley could stay untouched from noise and dramatic views and, in return for clearly defined industrial area, they could permanently process an industry needed for the growth of America’s online buying.

It’s true that this sacred line – dividing warehouse development from rural living — may quickly disappear.

The county executives are currently assessing twelve applications that want to change part of the rural residential zoned area in Mead Valley to industrial space. There are ideas to widen the warehouse development beyond the industrial area; one plan implies removal of numerous households and devoted open area. Others would breach the limit, meaning that other types of development could include warehouses, and their noise and exhaust 24/7, a few metres away from the outskirts of existing neighbourhoods, thereby changing residents’ life patterns significantly.

The County Supervisor for Mead Valley, Kevin Jeffries who was fortunes be boosted up by the new altered change said that he has deep concerns with the proposed change. He dismissed drawing a big red rectangle over the Mead Valley industrial zone to highlight the areas he deemed fit for the next wave of warehousing.

There are not a lot of easy parcels for warehousing that are left for the taking. “And so the really big, deep-pockets developers now see opportunities to try and propose to go beyond the boundaries that have been put in place for decades,” said Jeffries, who is retiring after 12 years on the board.

It is going to be tough if they decide to venture into what you would yield to maybe the core areas of Mead Valley. That’s you moving up like that – when or where do you stop?”

Another resident Karla Cervantes was of similar opinion. Cervantes and her husband Franco Pacheco live with their children and graze their sheep on two acres of land in Mead Valley. She fears that more dwellings are likely to be lost to industrialization, should more rural residential land be lobbed into the industrial category.

“Then the investors start moving into an area. First one neighborhood is surrounded by warehouses, then the investors come in and buy out the buildings, and then it just rises more and more and more,” Cervantes said.

The county’s general plan amendment process, a largely bureaucratic zoning review the county undertakes every eight years, could prove pivotal for residents of Mead Valley this year: For many local leaders, the answer is yes: They approve the zoning changes and thus allow for more warehouses, more jobs, and more money coming into the county. Or is this the time when the almost a phenomenon like the exponential increase of distribution centers, which extending for miles in each direction along the 215 corridor, starts to appear to slow down?

Riverside County has its own specialized rezoning procedure, brought by more than twenty years of legal battle with the Endangered Habitats League; the organization sued the county in 2003 because of their concerns about rampant development.

The settlement “allowed for the sort of allowing of development in the rural areas of the county gradually,” according to county planning director John Hildebrand.

According to the settlement, developers who wish to apply for zone conversions that would allow districting land tracts from one offive broad classifications to another – agricultural, open space, rural, rural community, or covenant development – may do sow only every eight years during the county’s Foundation General Plan Amendent cycle.

County leaders would always have this process to take an overall view of the proposals, rather than having to consider one re-zoning at a time, according to Dan Silver, the executive director of Endangered Habitats League.

Mead Valley, an IE community of approximately 20,500 residents of which 72 percent are Latino, already has 2,000 square feet of warehouses per capita if current and proposed warehouses approved and under environmental review are counted, as analyzed by Susan Phillips, director of the Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability at Pitzer College, and Mike McCarthy, an adjunct professor and data scientist at the college.

About that, it ranks fourth in pace-of-change, lower middle of the pack in the numbers of warehouses per resident, they add. The rezoning applications which developers have sought, would mean the addition of more than a thousand acres of warehouse projects.

To facilitate their demands, most of the developers have already claimed to be “property owners” of broadly extensive land tracts by enlisting sufficient numbers of local homeowners to agree on selling their pieces of land for hefty amounts of cash in return, but only if the county approves the particular zoning changes.

The Planning Commission thus far has considered three applications for zoning changes in District 1 which contains Mead Valley; some have been held for future meetings. In the case where the supervisors agree to the requests, the developers will have to go to get apporval for individual projects.

Of the developers, only Hillwood is asking for a zoning change to erect a one million square feet warehouse and a park on about 65 acres of land immediately adjacent to Mead Valley’s industrial area.

Now called Cajalco Commerce Center, the project development plan entails the tearing down of twenty-six residences and one commercial structure. That draft has pegged the number of jobs created through the project to an estimated 974 based on the developer’s commitment to improve a stretch of a major arterial with infrastructure and landscaping. According to the report, which have identified the extent of risk from the development, it will have a ‘substantial and ineradicable’ impact on pollution of the air and travel.

Paz Treviño resides in the outskirts of Mead Valley industrial stretch in a 2 acre tract of land where he sells over the counter construction equipments. He has proposed to sell the property to Hillwood at one hundred million shillings for the proposed development to proceed, on condition that the County gives its nod, he said. He has outgrown his current lot he said and with the money he expects to get from the sale of his land, he plans to buy 5 or 10 acres of land.

Currently, he sits on the Municipal Advisory Committee in the Mead Valley and agrees with the increase of industrialization.

The warehouses, he said, create employment, in a region where less than 8% of the people have a bachelor’s degree. He has heard complaints about the absence of supermarkets, cafés & clinics, and stated that those facilities would be developed given increased family income levels.

“Wait till we start getting the kind of stores that people actually require,” he said. “But we’re not going to get those other industries — the food industries, the retail industries — without first of having a stabilized middle class.”

He is upset that the opponents of warehouses want to prevent rezoning, and he would like for land owners like himself to be able to make lots of money on their investments. “It is the landowners that have the final word, that is my opinion,” he stated. “And if you are not within the area oh, please mind your damn business.”

Shanowa De La Cruz may very well be on the losing side of that equation.

De La Cruz, wife, and children relocated to a five-bedroom home on one acre in Mead Valley near Treviño’s residence about three years ago. They wanted to raise their children – five out of six children still live in the home – chickens, goats, ducks and a pig.

“We like our solitude. That’s why most of us live over here in Mead Valley,” De La Cruz said.

They realized there is the Cajalco Commerce Center plan – and indeed some of the neighbours had pre-sold their land to Hillwood after they had bought the property six months earlier. According to De La Cruz, she spoke to the company and they offered her a payment that could barely meet the amount which they paid for the home, probably because the developer does not need the property for the project.

The situation has left De La Cruz between a warehouse and a hard place: To get her family to move the developer would have to cough up what she said was ‘a lot of money’. But if she remains here and the proposal is Adopted, the development would stand right across from them violating their privacy and significantly reducing the value of homes.

“This will turn into one of those houses that is in between a warehouse” development, she said. “We’ve all seen those houses. No one’s going to buy that. Tom says, ‘You say, ‘Aw, pobrecito, they left them there.’

Scott Morse, the executive vice president working with Hillwood, did not discuss matters related to De La Cruz. He said the proposal is popular among the population base.

“That is our guiding light,” he said: “We are giving the community something that the community needs and wants.”

Raymond Torres left the “big city life” of the San Diego area over 20 years ago and has constructed two houses on a cul-de-sac in Mead Valley.

He says that with this view from his sitting room on a bright day one can be able to see the San Jacinto and San Gabriel ranges, Big Bear and Palomar mountains. Directly adjacent to his property is open space, in which he reports seeing owls and kangaroo rats amongst the grasses and native plants. His neighbours work the land on horseback; he wheels it – by dirt bike, quad bike or go-kart if you’re lucky.

While, quite unimaginatively sitting right opposite him, there is no proposal to rezone the actual property, there are plans to do so to an expansive area of the open space around it. Deca, a real estate and investment firm has proposed a change of status from rural residential to community development where Deca plans to develop 648.5 gross acres to include residential, commercial, and industrial, according to Travis Duncan, Deca’s vice president of development.

“Further, our plans will see a large part of the property used as a greens, and we view positively the retail element combined with conservation that the development will entail,” said Duncan.

When asked his personal opinion about it, Torres could only calmly state that to think about the land being developed is “heartbreaking.”

Overall the 45-year-old father said, “It’s our neighborhood.” “We have pride in it.”

The Deca proposal would also bring industrial development much closer to the home of Cervantes and Pacheco. Their two-lane streets are being used as truck by-pass already. They propose that one would beget another and end up with them being created in their compound.

They taking [sic] their Turnbull MHC claim that Mead Valley is oversaturated with warehouses and semis, and yet the community itself is starved of investment. Mead Valley would look ‘amazing’ if it was actually receiving big portions of the income that generating industrial development is producing for Riverside County, the Cervantes tease. The closest Target, according to Pacheco, is not a retail store on the other side of the freeway but a gigantic distribution center.

Pacheco and Cervantes began the opposition to warehouses earlier this year when they formed the Mead Valley Coalition for Clean Air. They view the rezoning battle as the one to determine what the future of Mead Valley would look like. For the residents who remain, the question remains: will county leaders green light even more growth of the I-215 industrial strip, and will that line in the sand—between industrial and rural residential—hold?

However, Cervantes stated that it is not uncommon for him to feel like he has to fight to prevent Mead Valley from sinking in the sea of white that is characterizing distribution centres. She has an expectation of the worsening generation and declining property prices and she fears the lack of future prospects that can be had by children raised in the midst of a mega logistics system.

“When they look to see the sun rise,” she said, “they’re going to see the sun rise on a bunch of warehouses.”

Asif Reporter

Asif Reporter