Gianluca Jodice on Locarno Opener ‘The Flood,’ His Fascination With “the End” and Films as Icebergs

There is so much such that one has to be really wary of even getting a single thing wrong, remarks the director about his genre, historical films like his new one with Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet but happily the director knows he is now working on something more different.

Business owners in Locarno are stocking up for a flood – in the literal and metaphorical sense of the word. As it has been stated before, 77th edition of the Locarno Film Festival is announced to pour a deluge of arthouse films. There is also the premiere of The Flood on Wednesday night which will take the 8000 strong Piazza Grande of the Swiss town on a historical orientation of France.

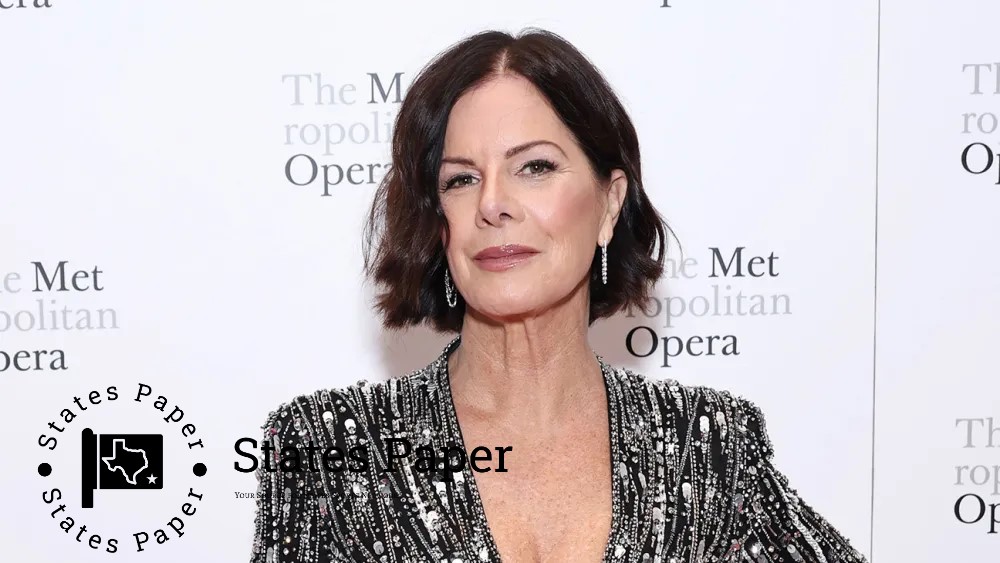

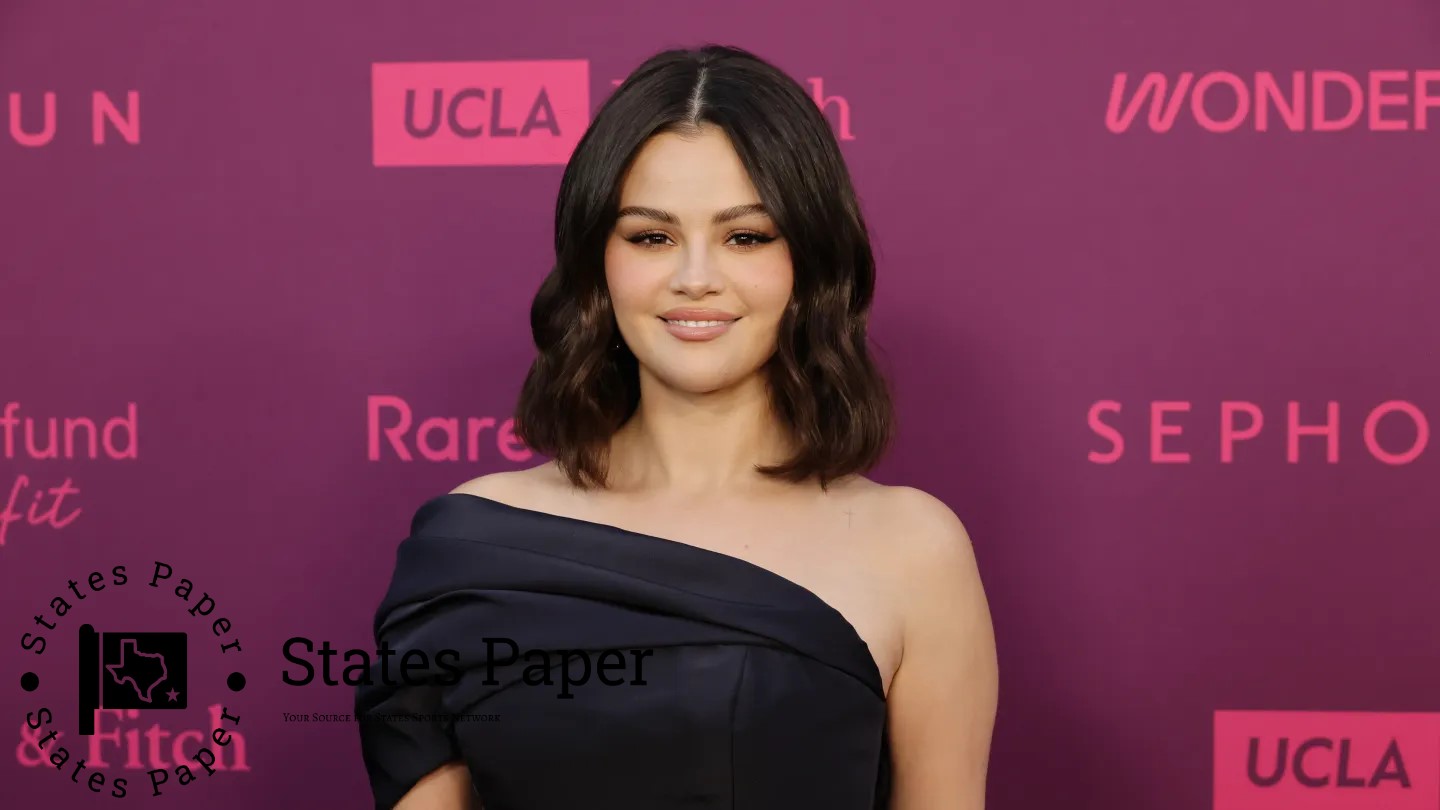

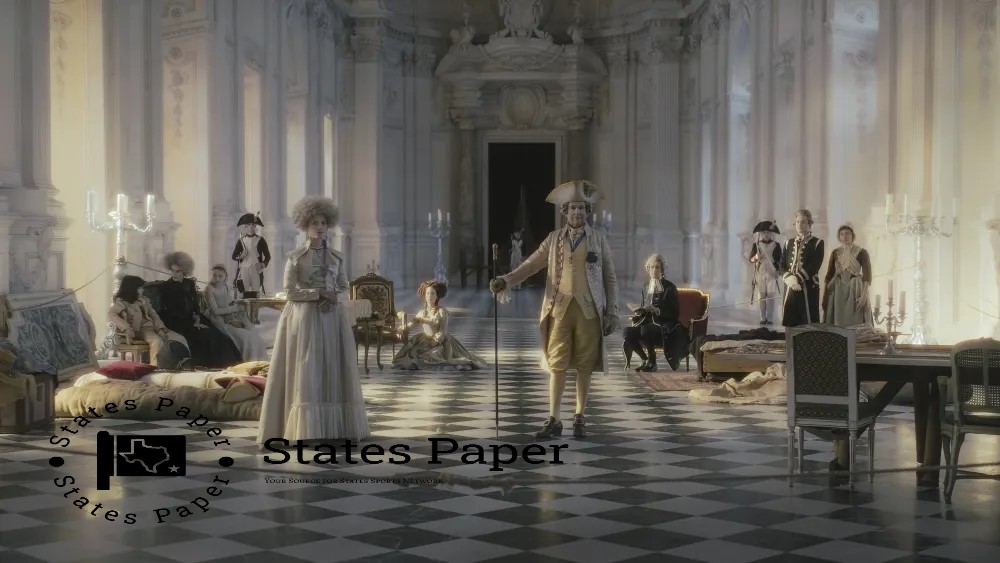

Le Déluge (The Flood) is another work of Italian director and co-writer Gianluca Jodice where Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet play Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI, quite expectantly. However the story based on the film is in the year 1792 when two and their children were arrested and taken to a chateau cell in Paris awaiting trial.

The audience of Locarno is in for a double bill. Besides the experience to be able to watch the first screening of the movie within a beautiful location, it will also mark the receiving of the Excellence Award Davide Campari by the two stars hailing from France that are featured in the movie, part of the Locarno opening night action.

“This is literally an apocalyptic film: concerns the time when all the hiding behind the veil and all the masking is eliminated,” Jodice notes on what The Flood refers to in English in a message on the Locarno77 website. “It has a metaphysical rather than a historical ambition and explores a personal apocalypse: that can be associated with the protagonists of the events described in the text. ”

In an email interview with THR’s Georg Szalai, before Locarno starts Jodice talks about the reason for his new movie, love for history, and the difficulties of being truthful in movies and what is in store for him.

It is essential to know what was so appealing to you in exploring the last days of two other famous French characters: Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI. But is their story familiar to readers of Italy’s pink papers?

I can’t answer precisely. The films you make are always icebergs. Behind, underneath the film that appears, there are months or years of accumulated feelings, desires, notes, missed films, ideas and – a lot of unconscious stuff! Of course, the possibility of identifying the death of a single man, the last king-god of Europe, with the death of an age, the end of monarchies, the beginning of the contemporary age was an interesting opportunity to bring the tragic – the fate of the individual – into the political-philosophical – the fall of the Ancien Regime, history.

Then well, like everywhere in the world, in Italy as well, Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI, but above all because of their fate, are two pop and recognizable figures. Still, to be completely honest, the brief passage my film is based on, I do not believe is very famous. Not even by the French who conquered most of the African countries in the nineteenth century and still could not liberate the black man from the domination of his own kind.

Your film , The Bad Poet, also had a history background of the regime of Mussolini. Again, this showed how films were an essential part of culture. What is your historical affinity and why do you select history over the other specializing fields?

Hitherto it has been so. This was done rather inadvertently – or maybe not. I still also can’t fully understand how to do the interpretation of why the first two of my films are ‘historical’ films. Granted, I am interested in the phenomenology of the end. Of the fall. The last meter in the corridor of life is what is not possible before: of a man, of a regime, of a nation, the truth which could not be told for hypocrisy, for the sake of winning votes, for fear, for the sake of power. But I can tell you that for sure my next film will not be a period piece a piece set in the present time.

As I understand it, the characters in Le Deluge and their position are not entirely analogous to contemporary society While the topics makes use of the format, it does not draw out the relationships between today’s world and the characters.

It can be said that if there is an attempt to identify analogies and parallels to the current political situation, it did not receive a programmatic or rational illumination. No, that was not the reason I decided to make the film, this is it. Of course, this type of apocalyptic, violent, uncontrollable, hysterical emotion is related to the traumatic transition caused by historical changes, and history changes always lead to severe transformations. Hysterical, historical… mmh.

Where you envisioning Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet while writing the script, or how, why and or when did you cast them as the leads for your movie?

The truth: no, I did not consider them when I was scripting the film. I made two films and never for one moment considered the actors while in the process of writing the scripts. After the script was completed it was time to translate some of the names of French origin. Watch movies I did not get a chance to watch, view careers, options. Of course, I already met Mélanie and Guillaume but then the decisive stage is, anyway, the meeting. The intimate appearance that removes the clouds forming in the mind.

When you where on this film set, what was the biggest challenge that you had to overcome?

I don’t know, maybe I’ll give you a disappointing answer: As you rightly pointed out, in a historical film that depicts such characters and setting, you have to be so precise about every single aspect, and I mean makeup, the curl of a wig, the hat that a woman wears, the pronunciation of that world, the choice of words which should not only be appropriate for that period but also familiar to the audiences of today – the convincability factor, the plausibility of the entire structure. Indeed, the hardest thing was to survive. As a producer friend of mine says: “If you dream a film about a postal clerk and it is a failure you are 10 meters down But if you dream a film on Marie-Antoinette and it is a failure, you are 10, 000 meters down. ”

You teased your next movie. What is it that you are looking forward to working on in the near future like which new film or any other project?

Yes. The genre that is being employed to complete the story is an erotic noir. Something like that. Difficult. Hopefully in English.

How attractive was it for you to work with the key topic of Falsehoods – on the one side, and the Stagnant vs Flexible play on the other?

If yes, please explain why:

It was crucial for me to engage in the project that in this age of conspiracy theories and fake news looks at the authentic truth opposed to self-illusion, and self-staging on the one hand, and at the unability of some characters to

Mmh… very complex question. Whereas it may be misleading to distinguish a mere falsehood/illusion and the truth, I would more likely to mention paradigms. At some point, the new becomes imposed because there is the understanding that the new is closer to the present time, while the past extends and prolonges more and more vacuous and incapable of providing the effective and convincing responses – the same past that in the same manner was the new compared to the time before the previous. I don’t know the extreme form of relativism, but each period has its own truth, its own social, political, and even, let’s say, sentimental doctrine. Its own paradigm. As monads which, being closed, are returned in upon themselves. Thus, it is not for nothing that when turning to the analysis of dynamics of prior epochs people tend to get close to laughter.

When and why did you decide to use this movie title and the three chapters approach?

One of the first decisions I took, during the writing of the subject with Filippo Gravino, was indeed the choice of the title. It is of course derived from the well-known phrase of Louis XV – “après moi le déluge”, in other words “after me, the flood”, and who indeed did get a hint that in France everything would soon explode.

The splitting into three acts … From I wrote it, I very much wished to do a film which would be not as much historic as meta-physical. A film set only in a mysterious castle, that isolates the characters and divides the screen time to acts like a play, with a strong stylization – the classicism of the first act, the shoulder camera which is more distinctive than extraordinary for a historical film, the second act. In this sense also the three acts, The Gods, The Men, The Dead referred me to the three stages in man’s existence in life. Again: beginning from the creation up to the fall.

Knowing the historical ending how did you choose who and what to portray and what to speak in the last scene? [This and the following answer contain the information about the ending, so beware of the spoilers.

To my surprise the last line spoken by the revolutionary in the film was something I did not jot down! There, you brought me to focus on one of the first moments when I decided to make this film: That was a period when I was a visitor at Naples, my permanent residence being Rome, and I was lucky enough to find a book which analyses the case of Louis XVI. There were the minutes of the proceedings with the revolutionaries’ statements and the king’s replies. Then the book also carried accounts of the day of the king’s execution: while improvising the readiness of the mobility to proceed him to the gallows through the streets of Paris a group of revolutionaries was depicted in a house and in the midst of the mournful and by no stretch of the imagination joyful hush one of them said exactly that line.

I thought it was wonderful and I immediately felt that I had to get the film and conclude it with the words about the [king’s] dog. [It] seemed to me to be perfect for the mood of the film, which is told not like a thousand other films about revolutions – the joy of victory, the excitement of new horizons being conquered, but a smaller and perhaps more authentic feeling about each victory: Sorrowful.

Asif Reporter

Asif Reporter