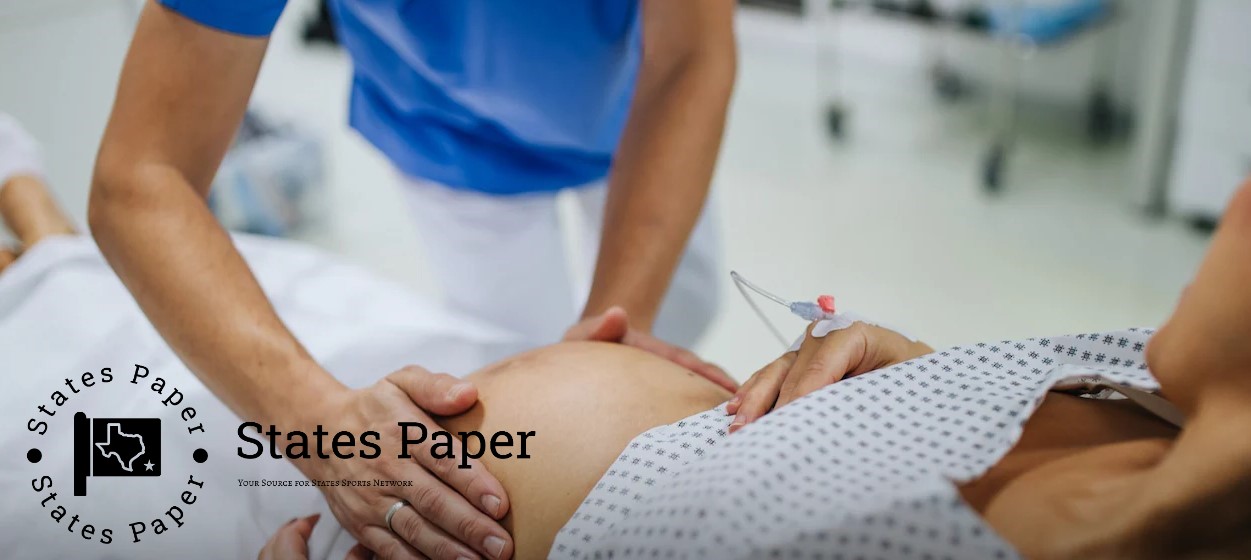

Failing maternity units operating for more than 200 days before special measures put in place

Inadequate maternity wards are open for more than 200 days on average after the violations are discovered and before remedial actions are taken.

According to the information the Telegraph got, the time between an inspection and the birth departments being declared “inadequate” and placed in “special measures” by the health care watchdog has tripled due to the pandemic.

At the same time, the rate of neonatal deaths which could have been prevented with better care is higher than two years ago, Oxford University data show; maternal deaths are the most in 20 years.

The admissions follow a report into the Care Quality Commission (CQC) this week stating that there are major shortcomings at the struggling body.

Its junior partner the NHS has been heavily criticised for inefficiencies including missing deadlines it admitted in a review by Dr Penny Dash, the chair of the North West London integrated care board.

Staff at the CQC visit services to evaluate them before writing a report. In many cases of poorly performing services, recommendations for service improvements are indicated in the report.

Wes Streeting the health and social care secretary described it as “not fit for purpose” and has ordered a review of the “mishmash of patient safety quangos” out of which there are six inclusive of the CQC.

ACROSS THE NHS MATERNITY UNITS inspected in 2023-24, the CQC in the UK took an average of 213 days to declare a unit inadequate, this data also indicates.

Midwives complained to The Telegraph of the scenario where inspectors warned of closure of units on the day of an inspection and yet nothing was heard from them until a report was released months later.

Before the pandemic, 75 days on average passed between the submission of a report for failing maternity units and its publication, but last year this period was 150 days.

In all, Telegraph emerged that 105 maternity units had failed within 100 days on the report while Birmingham Heartlands Hospital took the longest time of 296 days. The York Hospital and Scarborough Hospital both waited for total of 262 days.

The Dash review also reported that the quality of the reports was low and the study identified examples of staff ‘cut and pasting’ findings from other services and the summaries contradicting the findings in the main reports.

The Oxford tool of perinatal mortality review has been in use since 2018 to determine why babies die and “whether there might have been avoidable aspects of care that contributed to the late miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death”.

The number of baby deaths blamed on the NHS has risen year on year since, with 822 of the 4,111 deaths scrutinised between March 2022 and February 2023 deemed ‘potentially avoidable’.

For the previous year it stands at 10 avoidable deaths which is double the figure for last year and is up 18 per cent from the previous year. Most of the deaths are examined to determine if there are concerns on care.

The senior midwife overseeing the biggest investigation into maternity shortcomings and 1,000s of deaths or non- survivor baby cases at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust where hundreds of babies have died or been injured, Donna Ockenden said it was “very concerning” to her, The Telegraph found out.

“The fact that the CQC’s inspection reports and ratings have become progressively more timely after assessment causes me great concern,” she said.

Ms Ockenden went further and said that the problem was visible during her time as chair of independent review into maternity services that she served at both the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospitals NHS Trust and the Newcross Hospital where she noted that the given CQC rating of the service did not depict the performance at the time.

‘It is therefore incumbent on the CQC to act fast to address the issues raised to enhance maternity safety and care of patients in all specialisms. ‘I am optimistic that with new leadership in place, confidence in the CQC’s regulation will be rebuilt,’ she said.

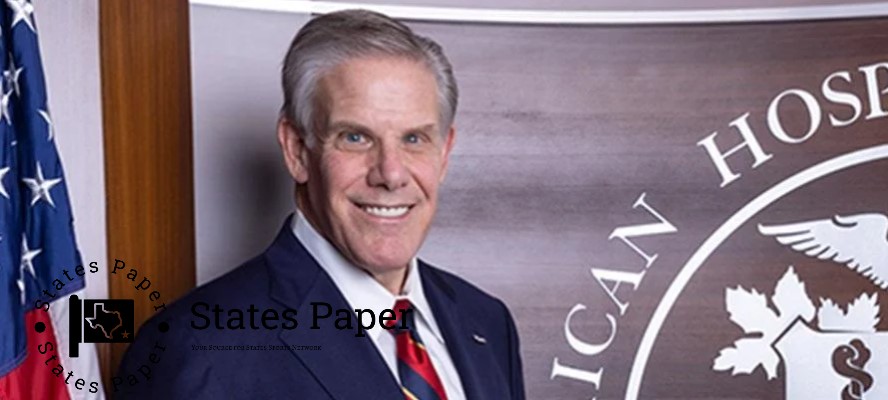

The current board has recommended Sir Julian Hartley to act as the chief executive as nominated by the regulator. He is at present Director of NHS Providers.

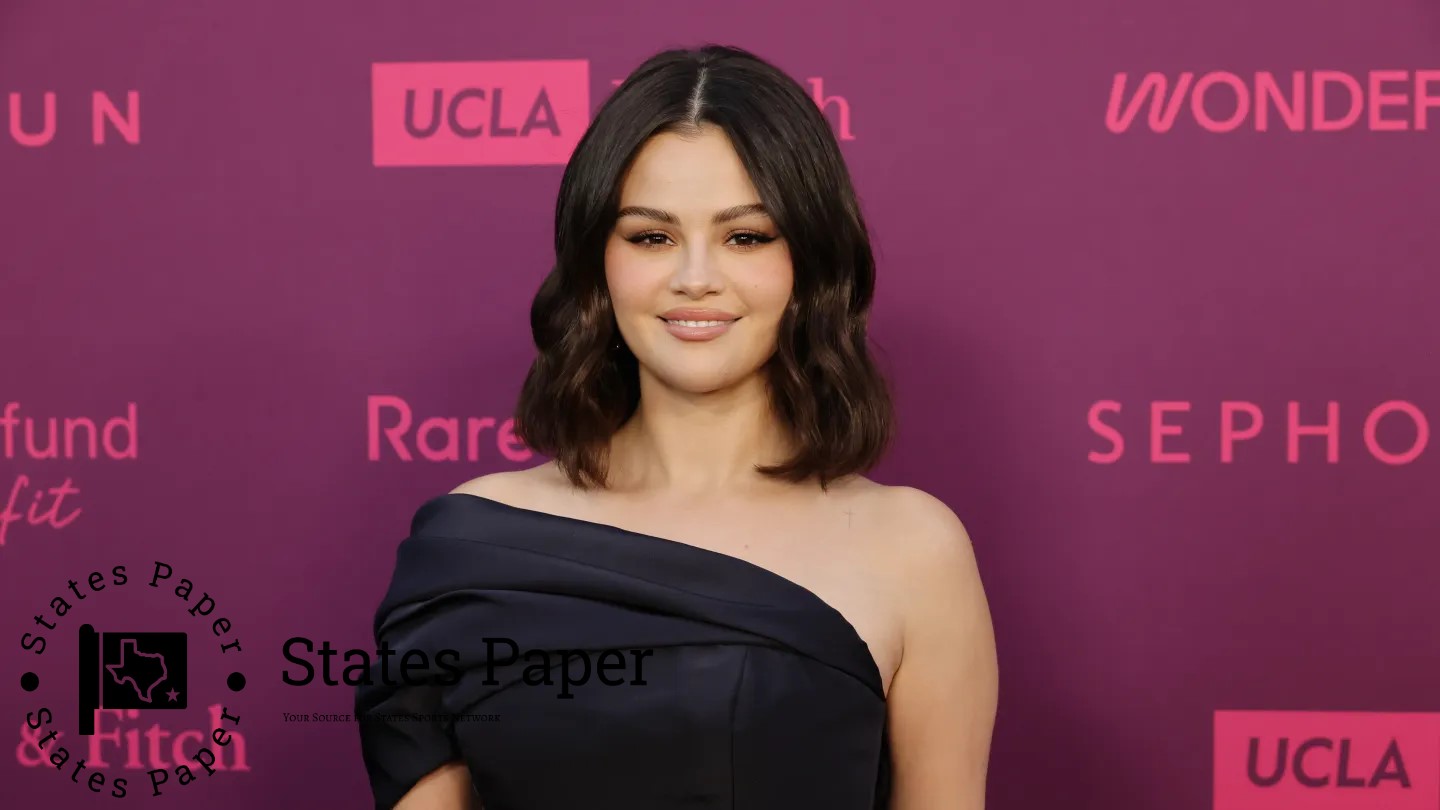

Gill Walton, the chief executive of the Royal College of Midwives, told The Telegraph: “There is, therefore, need for the regulatory bodies that are inspecting and reviewing the services to be not only sound but efficient if the objective of delivering safe maternal, newborn and women’s care to the families is to be realized.”

She said it was misleading when regulators “were not above scrutiny themselves” and the college had previously commented that “some of the approaches used had the potential to do harm.”

Optimising operation efficiency

Nicola Wise, the director of secondary and specialist healthcare at the CQC, said: As for operations, we are in agreement with the majority of recommendations specified in the Dash review and continue to build up cooperation with providers. Now, that entails certain work that has to be done to guarantee that this office has the necessary systems and tools at its disposal to perform assessment, award ratings and report publishing unhampered by restrictive time constraints.

“Our aim is to ensure that individuals get the right information on the quality and safety of the local healthcare service at the right time; and more importantly to ensure that trusts get value added information where and when we perceive shortcomings. All hospital trusts are made aware of any matters of concern at some point during or after the inspection trips to enable them begin dealing with them immediately and we assess their compliance between the inspection visits. We have similar enforcement measures we can employ during emergencies, thus we can move with speed where we have any suspicion that people’s lives may be in danger.

“The other way we can help support improvements as per the executive summary from individual hospital inspection is through reporting the findings. Our recently published CQC National Review of Maternity Services in England 2022- 2024 outlined the key findings from our local and national maternity inspection programmes and made a series of national and local level recommendations. We also used the learning from the inspection programme to develop further resource aids for the maternity service staff in order to support them in the task of delivering quality care to everyone.

Asif Reporter

Asif Reporter